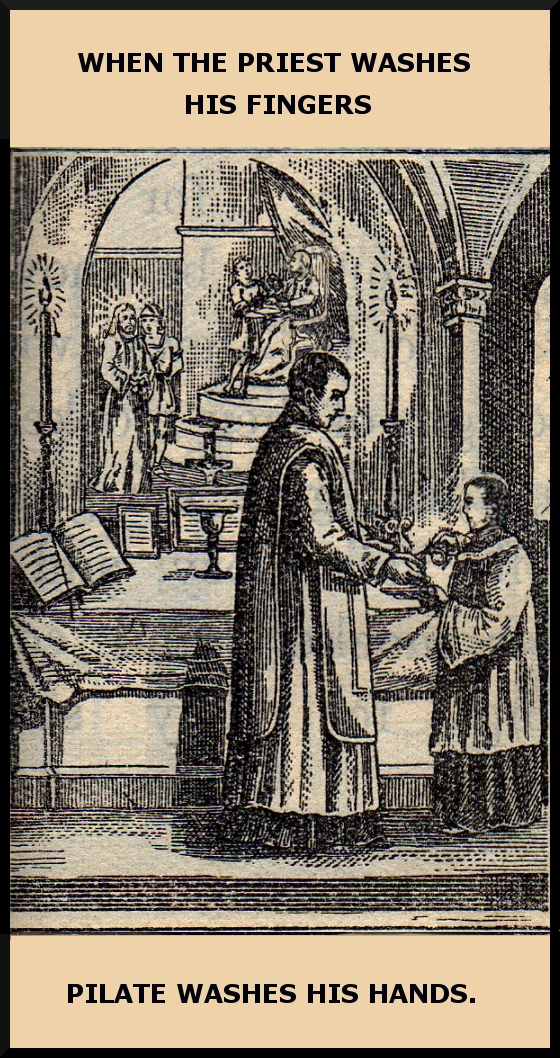

The washing of the hands is primarily a symbol of the interior purification necessary before offering the sacrifice of the Spotless Lamb. A good and humble priest, conscious of his unworthiness, must feel at this point a certain trepidation, for he knows that as “another Christ”, he must be pure of mind and body and blameless in his actions. Calmet comments on verse 7 of the Psalm ( Ps.25:6-12) which the priest prays at the Lavabo, that “God suffers no greater injury from any, than from bad ministers.”

The washing of the hands is primarily a symbol of the interior purification necessary before offering the sacrifice of the Spotless Lamb. A good and humble priest, conscious of his unworthiness, must feel at this point a certain trepidation, for he knows that as “another Christ”, he must be pure of mind and body and blameless in his actions. Calmet comments on verse 7 of the Psalm ( Ps.25:6-12) which the priest prays at the Lavabo, that “God suffers no greater injury from any, than from bad ministers.”

According to St. Thomas Aquinas (De anima iii) the hand is the “organ of organs” in which the power and activity of man is concentrated, used for either good or evil. In recalling that Pilate used that power to deliver the innocent Christ to death, we may pray: “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of the living God, who, though declared innocent by Pontius Pilate, didst hear without opening Thy divine lips, the outcries of the Jews to crucify Thee; grant that I may live innocently, and that the malice of others may not trouble me. Amen.”

In union with the priest and the other faithful, we propose to incline our wills to always do good so as to be counted among the innocent of heart who approach the altar.

For the Lavabo in the Novus Ordo, 7 verses of Psalm 25 were replaced with 1 verse of Psalm 51: “Lord, wash away my iniquity; cleanse me from my sin.” Consequently, there is no longer the priest’s protestation to God that he has the intent to “wash”– keep company – with the innocent of heart, because as the Haydock commentary states, doing so “is a great inducement to virtue”. Gone also is reference to “God’s wonderous works”; love of “the beauty of [God’s] House”; pleading with God to “Destroy not [the priest’s] soul with the wicked”. No more mentioned is the distinction between the innocent, and the wicked who are men of blood. Gone are many other expressions of filial supplication, gratitude and confidence in God.